"Testing sucks"

This was the general consensus amongst our group, and based on the data from Johnson and Richer, the consensus amongst surveyed teachers and students. While Johnson and Richer did not use the above terminology in their surveys, most data reflected that the majority of students struggled with standardized testing (PARCC), especially those from marginalized groups. Testing affected students' confidence, took away from meaningful instruction time, and pressured teachers as well.

In our discussions, we spoke about how race and SES impact testing, and seemed to agree that standardized testing maintains the historic status quo for power and privilege. Marginalized groups perform poorly on these tests, and high-stakes tests will serve to ensure these groups remain marginalized. More affluent SCWAAMP groups perform better overall and continue to receive full federal funding, accreditation, etc.

Despite the overwhelmingly negative responses to testing, we also spoke about the positives and necessities of testing. Testing can be a useful assessment tool when used in a way that is appropriate to a given population of students. There are many innovative alternatives to traditional tests which provide a more genuine sampling of ability than bubbling responses on a Scantron sheet.

In facilitating our group's discussion, I found what worked best was having class members attempt an exam in a language they didn't fully understand. This, I felt, gave us an opportunity to empathize with our students, especially ELLs, as they attempt to tackle such assessments. I also was glad to be able to show "Immersion," the story of Moises and his testing experience. I felt like I had some difficulty with timing-- allowing the small groups to run longer and taking away from the whole-group discussion. I also did not feel that plotting discussion points on the board was as productive as I'd hoped it to be. Nevertheless, I thought the facilitation went well and was definitely rewarding.

Chris Miller's SED 561 Blog

Saturday, December 16, 2017

Monday, November 13, 2017

Private Individuality vs. Public Identity

Reading through Collier, I had several agonizing flashbacks to preparing to take the Sheltered English Immersion MTEL exam (an exam I had to take three times before passing). Much of what she describes is best practice for ELL educators, specifically for bilingual educators. Attaining an SEI endorsement is challenging enough, but the demands for bilingual teachers are staggering. The quote that stood out to me the most highlights the less-academic challenges bilingual educators must face:

People untrained in linguistics, particularly politicians, tend to believe that if limited

English proficient students can converse with their monolingual English-speaking peers,

then these English-language learners can compete with them on an equal footing. (225)

This embodies so much of what’s wrong with the bureaucratic influences that dictate how our students are taught and how they are held accountable to perform on an “equal footing” on an imbalanced playing field. Conversational English (L2) proficiency is not the same as academic L2 proficiency (which holds true even if the student is a native English-speaker). Throughout Collier, which I read second, I kept coming back to Rodriguez’s “Aria,” whenever native language (L1) was pushed to the back burner in her examples of “what NOT to do.”

Rodriguez’s piece was the more engaging of the two articles for this week, especially in all the places where I saw language acquisition connecting to acquiring the tools of the culture of power (Delpit). Rodriguez’s story is a jarring example of how L2 acquisition can lead to lost proficiency in L1 and a diminished sense of culture, identity, and agency. L2 (English) becomes the culture of power, as it is the language of politics, education, and business. Without L2 proficiency, access to the culture of power is cut off; oftentimes, L1 is pushed aside in favor of acquiring L2, power, and a public identity. In considering how public identity is achieved by assimilating into the culture of power (in this case the language of power) I found myself asking, Does assimilation into public life always require losing a sense of private individuality? Then I thought about the implications of asking that question: Is my white, native English-speaking privilege allowing me to even ask such a question? My private individuality is so inline with the dominant ideal (SCWAAMP) of public individuality that I can’t dismiss my privilege here.

If you have time, please check out this “Immersion” short film if you’ve never seen it, it’s definitely worth the 12 minutes.

Monday, November 6, 2017

Pecha Kucha Presentation

My experience with Pecha Kucha has been limited to helping a very close friend prepare her own Pecha Kucha presentation by timing her slideshow and giving feedback. I remember the stress that went into keeping pace with the show, and that is my greatest area of concern now. I like the tips from the instructional video to use an outline instead of a script, but I know that my tendency to ramble or trail off might make sticking to the 20 second mark a challenge. Knowing the presentation through and through makes for a less anxiety-inducing presentation, but I feel like it is possible to overprepare. Still, the supportive culture that has been established in our class really eases any anxiety I have about presenting to my peers.

As for what I am going to do my Pecha Kucha on, I'm still undecided. My best idea going forwards is inspired by the Youth In Action presentation. It was definitely the most impactful part of this class thus far, and gave me some ideas as to how I can be a more effective advocate for social justice within my own classroom. At the program where I teach, the greatest deficit my students must overcome is the lack of stability in their lives. Integral to this is my students' almost universal lack of positive role models. Throughout the entire Y.I.A. presentation, the thought that nagged me most was how I wished my students could be there to hear those young women speak. Very rarely in their lives do they receive positive messages and inspiration, especially outside the program. I would like to more closely examine the potential benefits of having powerful examples of young women advocating for themselves and how the exposure to these examples could benefit my classroom population. I would also like to look into ways my program could provide residents with access to mentorship programs. Too often do messages come to my students only through the lenses of the media and the program, and I believe it would help my students' growth to have role models like the young women in Y.I.A. and similar programs.

As for what I am going to do my Pecha Kucha on, I'm still undecided. My best idea going forwards is inspired by the Youth In Action presentation. It was definitely the most impactful part of this class thus far, and gave me some ideas as to how I can be a more effective advocate for social justice within my own classroom. At the program where I teach, the greatest deficit my students must overcome is the lack of stability in their lives. Integral to this is my students' almost universal lack of positive role models. Throughout the entire Y.I.A. presentation, the thought that nagged me most was how I wished my students could be there to hear those young women speak. Very rarely in their lives do they receive positive messages and inspiration, especially outside the program. I would like to more closely examine the potential benefits of having powerful examples of young women advocating for themselves and how the exposure to these examples could benefit my classroom population. I would also like to look into ways my program could provide residents with access to mentorship programs. Too often do messages come to my students only through the lenses of the media and the program, and I believe it would help my students' growth to have role models like the young women in Y.I.A. and similar programs.

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

LGBT Message in the Classroom, or Lack Thereof

I did a bit of reflecting on my own experiences as I read through Vaccaro, August, and Kennedy and the GLSEN website. Throughout the Safe Spaces text, I paused several times at the “Reflection Points,” and asked myself the questions like “What messages did you receive about the LGBT community when you were in school?” (89) I did not like where this question took me: back to the early-2000s at an all-male Catholic high school. As an all-boys Catholic school, homosexuality was at or near the top of the list for taboos. At the time, expressions like “that’s gay” were common parlance and homophobic slurs were typical insults. Homosexuality was openly frowned upon, both in the religious and social spheres of the school, and several students were ostracized for even the slightest intimation that they were gay.

Homosexuality was an issue that was joked about, and many of my peers still seem to approach it with homophobia veiled in humor and the “whatever they do in their homes isn’t my business” line. Other than being exposed to changing representations of the LGBT community in the media, many members of my age group seem to have gained little insight into LGBT issues. The effects of curricula with little or no LGBT inclusion are evidenced in the continued pervasiveness of open and veiled homophobia.

Safe Spaces gives insight into how to address these issues in our classrooms with several dos and don’ts.

DO: use teachable moments to integrate or interpret the LGBT community

incorporate LGBT-inclusive texts

use inclusive language like “parents” instead of “mom and dad”

DON’T: conduct activities that can unintentionally erase the identities and realities of

marginalized students

remain silent in the presence of anti-LGBT statements

Reflecting on my experiences with LGBT marginalization as a high school student was troubling, but so was reflecting on my experiences thus far as a high school teacher. In my current position, I am limited in what I can reasonably do as an employee that needs a regular paycheck. The program explicitly prohibits relationships between residents, for mostly justifiable reasons, and discussion of LGBT issues is typically discouraged. Residents receive no instruction or insight into these issues through the program. My classroom library has been heavily censored by administrators, though I occasionally can work in a few LGBT-inclusive texts.

Monday, October 23, 2017

Power, Privilege, and Technology: Teaching Digital Literacy in Light of Digital “Haves and Have Nots”

Throughout

the readings for this week, I noticed the relationships between power, media,

digital literacy, privilege, and schooling. It was interesting and important to

revisit the concept of digital natives—a term I’m intimately familiar with. Having

been born after 1982, I consider myself (and am considered by the broad

definition) a digital native. Reading through Boyd, I did a lot of reflecting

on my privileged experiences with technology, and how many students who are

labeled as “digital natives” by the de facto criteria of birth year have vastly

different experiences with technology based on their lack of that privilege.

Growing up

in a middle-class, suburban, S.C.W.A.A.M.P. household, I had access to

technology at a pivotal time. It was the early 1990s, and my family had just

purchased a brand-spankin’-new IBM computer, complete with a massive 50MB hard

drive. I learned first how to launch my favorite computer games: “Prince of

Persia” and, when I could sneak it in, the staunchly-prohibited “Doom II.” I

then learned how to work the MS-DOS software by typing and executing commands,

such as “c:\>_runwin” to launch Windows 95. We eventually upgraded to a bigger,

better machine, complete with America On-Line and dial-up internet. The privileged

youth of the new millennium have similar experiences of navigating burgeoning

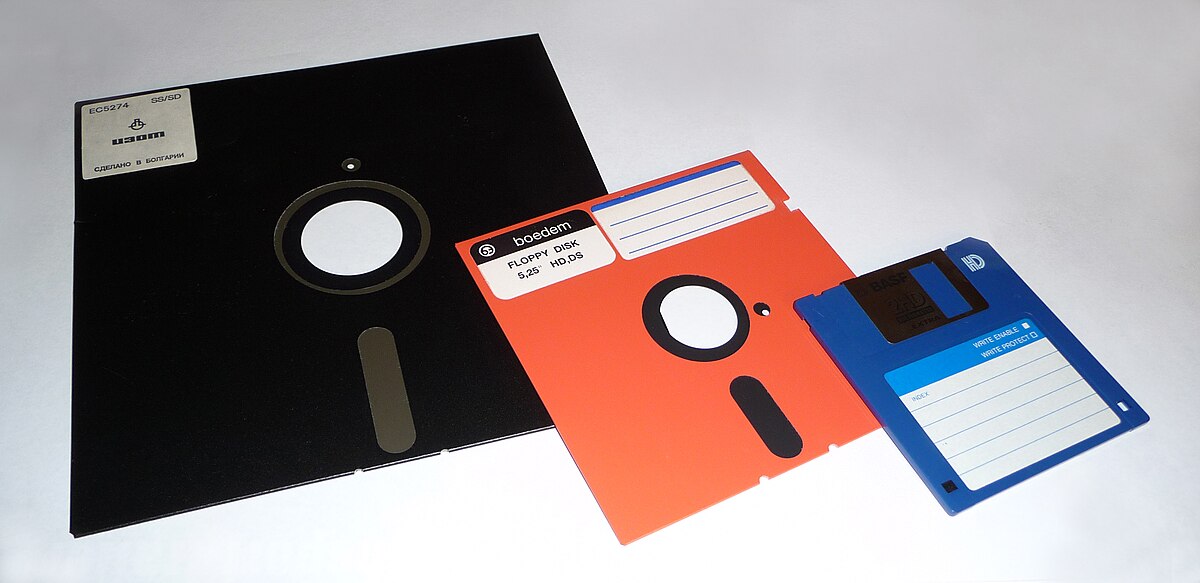

technologies, albeit with cloud storage instead of 3 ½ floppies and iPads

instead of GameBoys. Digital literacy often comes back to privilege and power.

The white

middle class student who grew up with the family’s IBM or Macintosh at his or

her disposal has the privilege. I look at my students, very few of whom even

have access to cell phones, and their inability to navigate technology is

telling of their lack of privilege and power. With privilege (i.e. the family

where all three children have a phone, tablet, and computer access) comes the

power of being “native.” This power opens many of the doors of “high-status opportunity,”

such as careers in technology, that remain closed to those without power (Boyd

198).

Even those with the power,

privilege, and iPads can be at a disadvantage when assumptions are made about

their digital competencies. Boyd makes an interesting case using Wikipedia and

Google to illustrate how off the mark youths (and adults) can be when trying to

think critically about information technologies. Despite being more democratic

and organic, Wikipedia continues to suffer from the paranoid assumptions that

much of its material is falsified or unverifiable. Having edit history and

discussion boards open to the public make Wikipedia much more transparent than Google,

with their corporate-influenced algorithms. There are opportunities missed when

the concepts behind Wikipedia are not taught. Wikipedia is the best

contemporary example of “how people produce knowledge” by coming together and

engaging in public debate (191). This transparent, non-corporate, open, and

collaborative practice is not found at Google (what are they REALLY doing with our search history and

GPS locations??), and is absolutely not found in Texas textbook publishers.

As educators trying to navigate

power, privilege, and technology, it is up to us to enable our students to reap

the benefits of widespread access to technology. The access alone is not

enough, and requires extensive instruction and support. Our students being born

into this world doesn’t automatically enable them to navigate it or critically

contribute to it (177). Marshall and Sensom reference a very useful analogy of

comparing our students to fish. As educators, we live in the same fish tank as

our students. As such, we must get them thinking about the water.

Monday, October 16, 2017

Challenging the Status Quo

Reading through Finn, I found myself nodding along in

agreement with much of what was said, but did not find anything groundbreaking

compared to what we have already read. “Teaching is a political act” is a quote

I first came across somewhere in my undergrad work, and I felt this piece

really embodied that idea to the fullest. What struck me most is how there are

everyday things that teachers do that are not viewed as controversial or seen

as “political” because they maintain the status quo. This made me reflective of

the times when I subconsciously maintain the status quo, especially when I fall

back on letting the text “teach” (I cringe to think about some of my World

History lessons last year), and the times when my colleagues and I break away

from the status quo and try something new, different, and progressive.

Breaking away from the status quo in my position (and in

many positions in teaching environments different from mine) is always a risky

venture, given my population and the school environment. We do it anyways,

taking calculated risks in an effort to do something real. The quote that stood

out to me the most, the one that I shared with a colleague this evening, is “’I’d

get into trouble’ is not an ethical reason why a professional does not make a

professional decision” (181). Still, I always need to be mindful of my

population (and my paycheck), especially when I get FIRED UP on social justice,

and pump the breaks a little bit. I don’t think Finn is advocating for blowing

the roof off the institution, but we do need to maintain that “attitude.”

In maintaining that attitude, we also need to be reflective

of the consequences of our political acts within the classroom, especially when

considering unintended outcomes. When Bigelow and Christensen reflected on

outcomes of sharing with their students that “there is a differential schooling

in America such that poor children are prepared to become poor adults and rich

children are prepared to become rich adults,” I thought, “That about sums it

up. Why not share that with my kids?” (182). Then I considered the unintended

outcome that they marked as their failure—that pressing such issues can

encourage students to see themselves as victims and present the obstacles as

hopeless. Our challenge is to present these issues in a way that advocates for

students to empower themselves to elevate their positions. We need to find that

balance of a classroom where “students have the maximum power that is legally

permitted and that they can socially handle” (175). For me, that balance may

lie on the more restrictive side than for other teachers, but I will still try

to open dialogue and possibilities for my students.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Seminar Facilitation Reflection

"Testing sucks" This was the general consensus amongst our group, and based on the data from Johnson and Richer, the consensus a...

-

The big idea that Nikole Hannah-Jones tries to get across in the work she shares on “The Problem We All Live With” is t...

-

Reading through Collier, I had several agonizing flashbacks to preparing to take the Sheltered English Immersion MTEL exam (an exam I had ...

-

I did a bit of reflecting on my own experiences as I read through Vaccaro, August, and Kennedy and the GLSEN website. Throughout the Sa...