Throughout

the readings for this week, I noticed the relationships between power, media,

digital literacy, privilege, and schooling. It was interesting and important to

revisit the concept of digital natives—a term I’m intimately familiar with. Having

been born after 1982, I consider myself (and am considered by the broad

definition) a digital native. Reading through Boyd, I did a lot of reflecting

on my privileged experiences with technology, and how many students who are

labeled as “digital natives” by the de facto criteria of birth year have vastly

different experiences with technology based on their lack of that privilege.

Growing up

in a middle-class, suburban, S.C.W.A.A.M.P. household, I had access to

technology at a pivotal time. It was the early 1990s, and my family had just

purchased a brand-spankin’-new IBM computer, complete with a massive 50MB hard

drive. I learned first how to launch my favorite computer games: “Prince of

Persia” and, when I could sneak it in, the staunchly-prohibited “Doom II.” I

then learned how to work the MS-DOS software by typing and executing commands,

such as “c:\>_runwin” to launch Windows 95. We eventually upgraded to a bigger,

better machine, complete with America On-Line and dial-up internet. The privileged

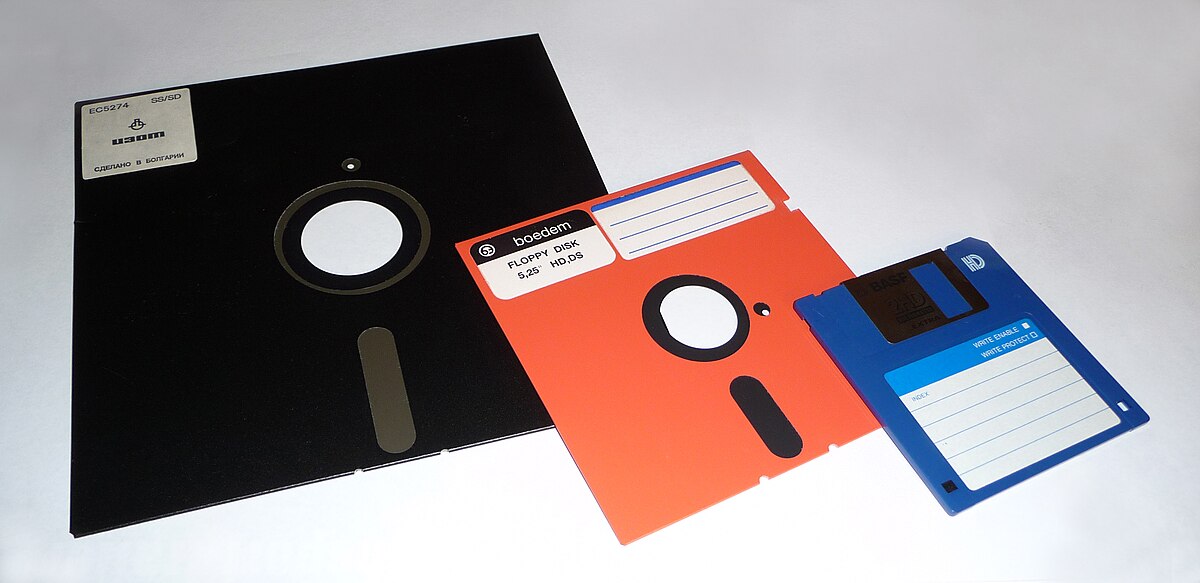

youth of the new millennium have similar experiences of navigating burgeoning

technologies, albeit with cloud storage instead of 3 ½ floppies and iPads

instead of GameBoys. Digital literacy often comes back to privilege and power.

The white

middle class student who grew up with the family’s IBM or Macintosh at his or

her disposal has the privilege. I look at my students, very few of whom even

have access to cell phones, and their inability to navigate technology is

telling of their lack of privilege and power. With privilege (i.e. the family

where all three children have a phone, tablet, and computer access) comes the

power of being “native.” This power opens many of the doors of “high-status opportunity,”

such as careers in technology, that remain closed to those without power (Boyd

198).

Even those with the power,

privilege, and iPads can be at a disadvantage when assumptions are made about

their digital competencies. Boyd makes an interesting case using Wikipedia and

Google to illustrate how off the mark youths (and adults) can be when trying to

think critically about information technologies. Despite being more democratic

and organic, Wikipedia continues to suffer from the paranoid assumptions that

much of its material is falsified or unverifiable. Having edit history and

discussion boards open to the public make Wikipedia much more transparent than Google,

with their corporate-influenced algorithms. There are opportunities missed when

the concepts behind Wikipedia are not taught. Wikipedia is the best

contemporary example of “how people produce knowledge” by coming together and

engaging in public debate (191). This transparent, non-corporate, open, and

collaborative practice is not found at Google (what are they REALLY doing with our search history and

GPS locations??), and is absolutely not found in Texas textbook publishers.

As educators trying to navigate

power, privilege, and technology, it is up to us to enable our students to reap

the benefits of widespread access to technology. The access alone is not

enough, and requires extensive instruction and support. Our students being born

into this world doesn’t automatically enable them to navigate it or critically

contribute to it (177). Marshall and Sensom reference a very useful analogy of

comparing our students to fish. As educators, we live in the same fish tank as

our students. As such, we must get them thinking about the water.

Hi Chris,

ReplyDeleteI liked how you took your own experiences into account when writing this post. I too started playing computer games as a young child. I remember having to go to use the library computers for several years once ours broke. However, we still had access to computer labs at my school (middle-upper class, predominantly White district). It is interesting to think about the different access kids have growing up. As a teacher at a school where students use computers, I can still see how some students are familiar with technology and others struggle.